Tariffs, Growth, and Brexit

Scott Sumner’s post Tariffs and the Economy observes that the most important effects of tariffs are not big, dramatic, or immediate ones. They’re the hits to long-term growth as arrangements gradually become less efficient and lower growth rates compound.

The lack of an immediate, catastrophic outcome could be used as an excuse to dismiss tariffs as not that big a deal. Even at the point of the biggest market losses after the Rose Garden tariff announcements, the S&P 500 was at far higher levels than it had been five years prior. A year’s lost wealth is a tragedy. Increasing wealth increases our potential to save and improve lives. But it’s true that the United States was quite rich five years ago and remains quite rich now.

This called to mind the ‘Brexit: Five Years Later’ takes in 2024. Brexit was the withdrawal of a smaller economy from integration with a large common market—essentially, introducing trade barriers.

In spring 2016, the UK Treasury forecast an “immediate and profound” recession if Brexit passed. When this didn’t happen, supporters of Leave started mocking “Brexit doom”, dismissing concerns that there would be a dramatic economic cost of leaving the EU. Aside from the general rule that shrinking the market makes us poorer (or we know almost nothing about economics), those dismissing the cost would have benefited from the more specific lesson in point three of Scott’s post:

And then, from points four and five:

4. The most important economic impact of tariffs is on long run economic growth. (There are other non-economic impacts, such as increased risk of war. 5. Most economists do not overestimate the impact of tariffs on long run growth.

Finally, the reminder that “A 0.2% decline in long run growth is far worse than a 2% fall in GDP for a single year.” (Read the whole post for more on the effects of monetary policy.)

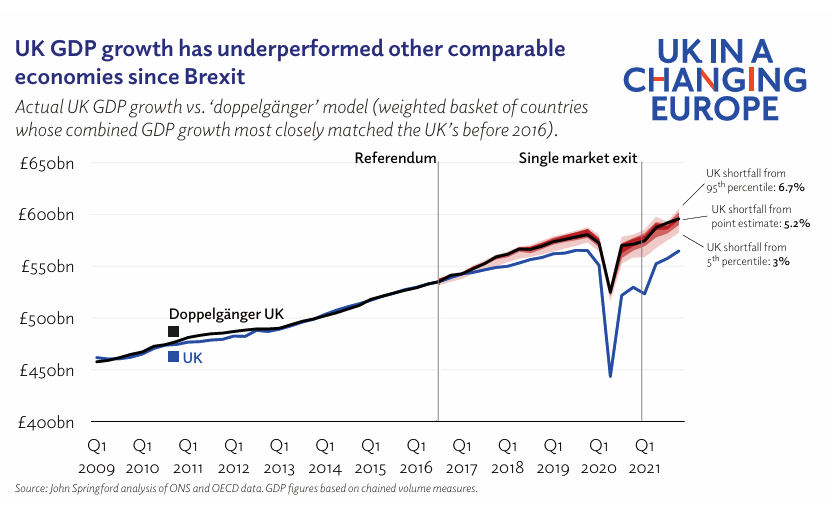

In longer run forecasts of the cost of Brexit, economists seem to have been closer to the mark. By January 2020, GDP was 1–3% lower than it would have been if the UK had not voted to leave the EU. By 2025, productivity is falling, and the UK economy seems to be underperforming in this ‘doppelgangar’ model (which takes the pandemic into account and is the model with the most fun name).

The Brexit Files: from referendum to reset, 28 Jan. 2025

The Brexit Files: from referendum to reset, 28 Jan. 2025

There are obvious differences between the United States and the UK. Probably most significant is the size of their populations and economies—the extent of the U.S. market is bigger to begin with. Brexit is also a harder policy to reverse than tariffs the U.S. president seems able to change on a whim. But the basic principle, the most basic in economics—that the division of labour, limited by the extent of the market, makes us richer—is still the one at play.

Either way, the important thing to remember is that no matter how dramatic the stock market tickers are, they’re not the most important part of the story. Even if all the tariffs were to be called off tomorrow, it’s hard to imagine how the U.S. could restore international trade given the economic uncertainty and political animosity they’ve permanently introduced.

econlib