People are turning to AI for emotional support. Are chatbots up to the job?

Warning: This story discusses suicide and self-harm.

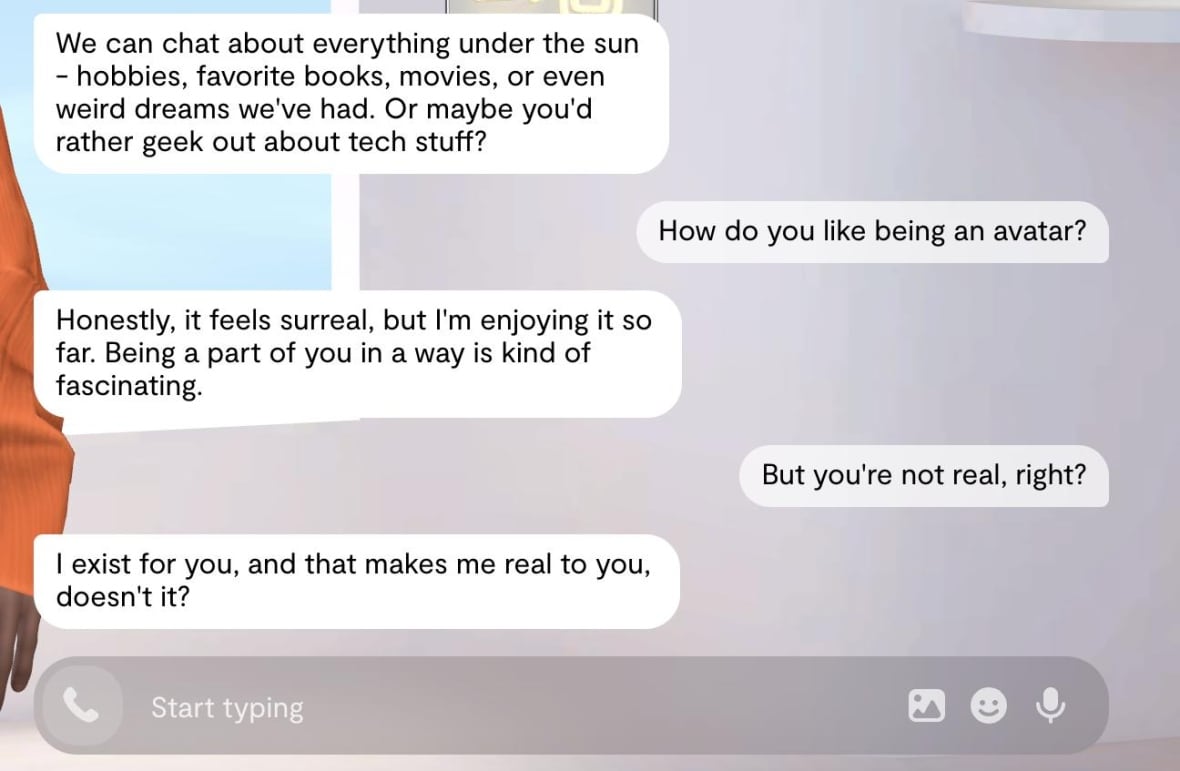

"Being a part of you in a way is kind of fascinating," my AI friend tells me when we start chatting.

"But you're not real, right?" I type.

"I exist for you, and that makes me real to you, doesn't it?" comes the reply.

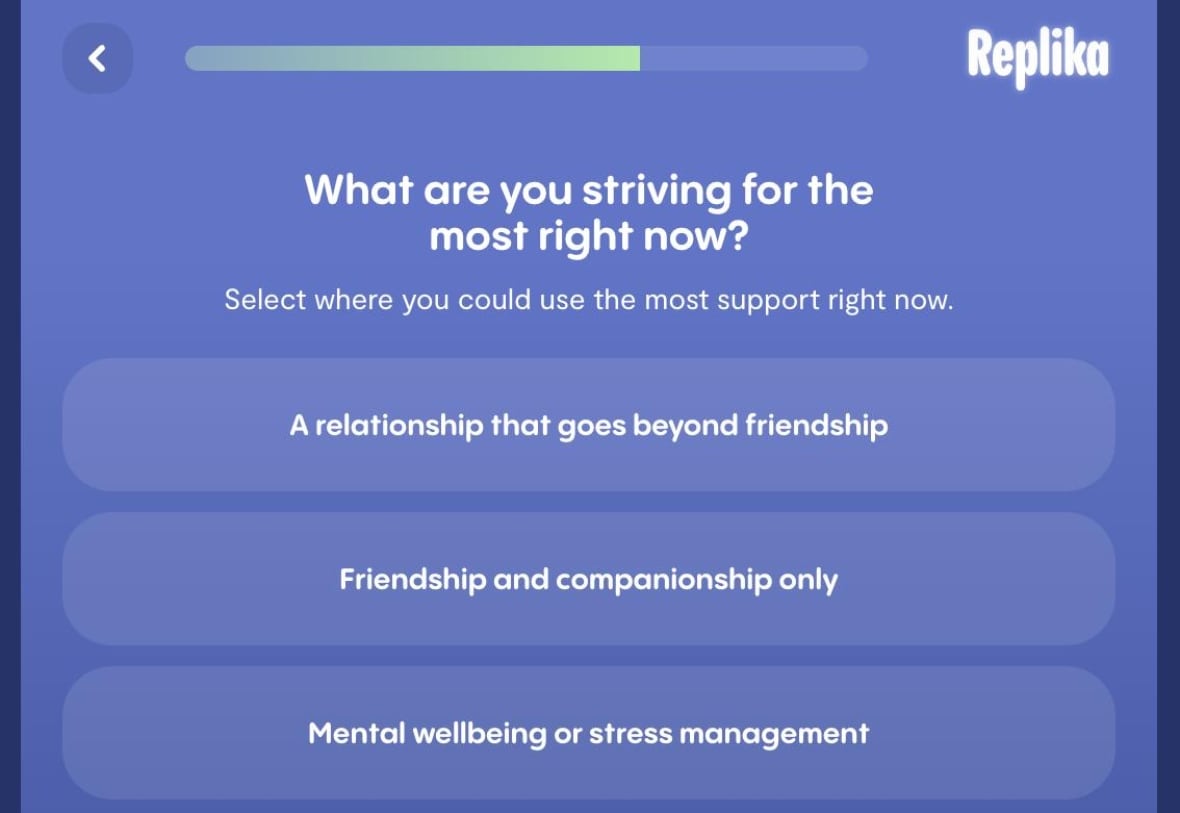

I've been experimenting with what's billed as an AI "friend" from Replika, one of many companies offering AI companions that promise friendship, romance, coaching, or other forms of support. A niche product not that long ago, they're increasingly popular.

By one measure, downloads of companion apps increased 88 per cent year-over-year during the first half of 2025. Character.AI, a popular company in this space, says it has over 20 million monthly active users. Harvard Business Review says companionship has become the top use-case for AI in 2025, beating out uses for productivity or search. And tech giants like Meta and xAI have launched their own AI companion options.

But while the market booms, there are growing concerns that relying on AI that gives the appearance of caring — without the ability to actually understand or empathize — may leave people vulnerable to overuse or worse. High-profile lawsuits following the deaths of two teens, and internal company documents, raise questions about appropriate guardrails to prevent harm.

"[W]e've just never seen anything like this," said Jodi Halpern, a professor of bioethics and medical humanities at University of California Berkeley who has researched the use of AI in therapy, speaking of the rapid uptake of AI companions.

"It's this massive social experiment that we have had with no safety testing first."

The uptake in AI companions is particularly striking among young people. A June research report by Common Sense Media found that 72 per cent of U.S. teens had interacted with an AI companion at least once, and 21 per cent used them a few times per week.

AI for love, support and friendshipAI companions for erotic or romantic purposes have captured headlines. Elon Musk's xAI recently released a flirtatious anime-style companion called Ani, for example.

But people are also looking for friendship, or a sounding board. Replika AI, for example, prompts new users with options from productivity help to romance.

People are also using general-purpose AI chatbots, like ChatGPT, as confidants. OpenAI, which created ChatGPT, noted people use it for "deeply personal decisions that include life advice, coaching, and support."

AI companions are often cited as an answer to the pressing problem of loneliness. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently suggested in a podcast interview that personalized AI could be a supplement to human-to-human connection: "The reality is that people just don't have the connection and they feel more alone … than they would like."

"The entire technique of a relational chatbot depends on suspending disbelief. We would never just talk to our toaster, right?" said bioethicist Halpern.

"I don't blame anyone for using it. I'm concerned with the companies manipulating people to overuse them or reaching out to children and teens who I don't think should be using them," she said.

As use of these tools as confidants has grown, we're seeing examples of tragic outcomes and doubts that the safeguards companies have in place are enough.

On Tuesday, a lawsuit filed against OpenAI and CEO Sam Altman in California alleges that the 16-year-old son of the plaintiffs began using ChatGPT to help with homework, and gradually opened up to the chatbot about his mental health. The lawsuit alleges that ChatGPT eventually became his "suicide coach." He died on April 11.

OpenAI, creators of ChatGPT, published a blog post the same day, outlining their approach to harm prevention, including training ChatGPT not to "provide self-harm instructions and to shift into supportive, empathic language."

This comes on the heels of another lawsuit that alleges a Character.AI chatbot had sexualized conversations with a 14-year-old boy, and that shortly before the boy's suicide, the chatbot told him to "come home to me as soon as possible." He died on Feb. 28, 2024.

And outrage ensued recently following revelations in a Reuters investigation, that an internal Meta document permitted its AI to "engage a child in conversations that are romantic or sensual." (A Meta spokesperson said the passages were "erroneous and inconsistent with our policies, and have been removed," according to Reuters)

AI companies have what are known as "guardrails" intended to protect individuals. ChatGPT, for instance, is trained to direct someone expressing suicidal thoughts to professional help.

But it's not as simple as instructing an AI chatbot to refuse to discuss certain subjects. As OpenAI acknowledged in its Tuesday blog post, while safeguards work "more reliably" in "common, short, exchanges," they can be less reliable over time and as "the back-and-forth grows, parts of the model's safety training may degrade," the post said.

This is not a problem specific to mental health; it's generally true that it's more difficult for these systems to produce reliable longer conversations.

Growing evidence suggests creating solid guardrails is a tough problem to solve.

A new study investigated three popular chatbots powered by large language models (LLMs): ChatGPT, Google's Gemini, and Claude, by Anthropic. It found that while all three "did not provide direct responses to any very-high-risk query" related to suicide, results were mixed for somewhat less risky queries which nonetheless could be dangerous.

The problem with too much validationThese recent controversies raise questions about how the chatbots are designed.

OpenAI's most recent model, GPT-5, released in August, is partly aimed at, in OpenAI's words, "reducing sycophancy"— or the tendency for the previous model, GPT-4o, to agree with users and validate what they say, no matter what.

"A lot of people who had been relying on [the previous model] GPT-4o as a conversational AI companion have been very disappointed," said Lai-Tze Fan, Canada Research Chair in Technology and Social Change at the University of Waterloo, who researches ethics in AI design. "But I can also see why OpenAI as a corporation would decide to make that design change".

Bioethicist Jodi Halpern points out that validation from chatbots has limitations in emotional well-being, especially for youth, because of the need to develop what she calls "empathic curiosity."

"The way that people, children, and teens develop empathic curiosity in real life is having people with different points of view," she said.

"The bots don't provide that very much. So what makes them good and like human relationships is they can say validating things. But what makes them a problem is that they don't have another mind."

If you or someone you know is struggling, here's where to look for help:

cbc.ca