Eternal Grudges. The Lesson of Ferruzzi and Gardini

Ansa photo

Magazine

The "builder" and the "player." Revisiting the Enimont adventure to shed light on the debacle of "Italian-style capitalism."

On the same topic:

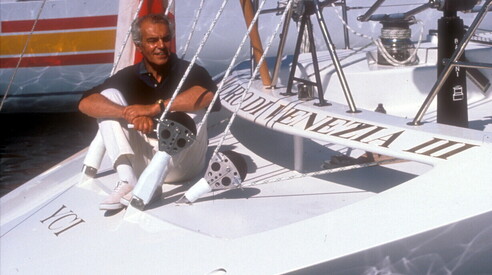

The wife, Idina Ferruzzi was always convinced: "He felt abandoned, but it wasn't like him to take his own life." Yet it was him, it was Raul, who said, "I don't want anyone else." To end up in prison, a sailor, a great navigator, the helmsman of the Moro di Venezia? No kidding. According to Antonio Di Pietro, suicide was "an act of desperation, of defiance, a final act by a great protagonist. There was a sea of things he had to come and tell the judiciary." And he had to do so on the very morning of July 23, 1993, when, in Milan, in the apartment on Piazza Belgioioso, Gardini, still wrapped in his bathrobe, grabbed his pistol, a Walther PPK, and fired the fatal shot. Three hundred meters away, in the church of San Babila, the funeral of Gabriele Cagliari, president of Eni, was being held. He had been found on July 20 in the bathroom of his cell in the San Vittore prison, suffocated by a plastic bag. Those two suicides, just three days apart, are still being questioned, questioned, researched, written about, and published. Reconstructions of Italian capitalist families, unhappy despite their wealth and, with all due respect to Leo Tolstoy, equally unhappy, abound, full of losers who denounce the abuses they suffered and long to recount a reality buried in opportunistic oblivion . Archives are opened, safes are flung open, documents, reports, long-forgotten letters, and seemingly unimportant notes are brought out of drawers. And books are printed to put their truth down in black and white. There is always a wrong to right, an unfair, sometimes immoral, defeat, an individual success that has become a general downfall, there is always someone who has reached the "peak of their incompetence" only to fall inexorably, as in the Peter Principle. It's true in politics as in business, it's true whenever combining the cunning of the fox with the strength of the lion isn't enough; or when neither audacity nor fortune can fill the lack of virtue.

Giuseppe Caprotti, Bernardo's son, brutally ousted by his father while he was at the helm of Esselunga and marginalized by his stepmother Giuliana, the main heir along with her daughter Marina, wrote his true-to-life book: "The Bones of the Caprottis," published in 2023 by Feltrinelli. The year before, journalist Tommaso Ebhardt had published Leonardo Del Vecchio's heroic biography, while the heirs were divided (and still are) over the role of Francesco Milleri, appointed undisputed lifelong boss. But the wounds that bleed even more are those of the Ferruzzis. Thirty years after Gardini's death, painful recollections have flourished. The reprint of the long interview given to Cesare Peruzzi, titled "A modo mio" (Baldini + Castoldi), had attracted renewed attention . No one except Il Foglio ("The Forgotten Serafino," July 29, 2023) had remembered who had accumulated the vast wealth squandered on dreams and adventures marked by unrealistic grandeur. Carlo Sama (husband of Alessandra Ferruzzi, Serafino's youngest daughter), Gardini's longtime right-hand man, published his version last year with Rizzoli, titled "The Fall of an Empire," which specifically criticizes the liquidation decided and carried out by Cuccia's Mediobanca.

Now it's up to a historian, Luciano Segreto, to reconstruct with extreme precision the last great debacle of Italian-style capitalism. The book is titled "The Builder and the Player," published by Feltrinelli. It's the latest in a series, but it's not a mass-produced book. It sheds light on many aspects that have remained obscure, those of Serafino "the Builder" and Raul "the Player," or perhaps he should be called the Destroyer, the man who in a single year between 1992 and 1993 burned through 2,400 billion lire, ruining the entire Ferruzzi-Montedison group, Italy's second-largest company after Fiat. When he left his post in 1991 to "sail other seas, with another wind," he took a severance package of 505 billion lire and kept all his other benefits. But let's not jump to conclusions. On December 10, 1979, Serafino died in a crash of his private plane in Forlì. According to Gianni Agnelli, he was the richest man in Italy. His wealth is difficult to calculate, partly because it was immobile, though not unproductive, on agricultural holdings in Italy and South America; partly because it was the fruit of the ever-uncertain grain trading business, for which he had become renowned even on the Chicago Stock Exchange; and partly because it was hidden in the Swiss fund managed by the faithful Giuseppe "Pino" Berlini (there is talk of 1,250 billion lire in cash, and there are no documents). The "builder" left a full wallet to his eldest son Arturo and his three daughters Ida, Franca, and Alessandra, but a void at the top of the group he had always run like a domineering father . Ida's husband, Raul Gardini, 46, an ambitious and charming agricultural expert, with one eye half-closed due to an illness, ptosis (his enemies called him the Pirate), a man of few words and broad smiles, seized power in a veritable coup. The entire family bows to him, with the only partial exceptions of Alessandra, the only one with a degree (in economics), and Sama; even her objections, too feeble in truth, melt away on the family altar.

Segreto devotes 76 of the 427 pages to Serafino and his irresistible rise, not without interesting new developments. The rest inevitably deals with Gardini's solitary and desperate journey and the dismantling of the group. The elder Cuccia and the trusty Maranghi acted as liquidators and bankers, but they found no industrialists willing to enter such a vast and varied universe: from wheat to soybeans, from agricultural companies to cement factories, from sugar to antibiotics, from real estate to television (Telemontecarlo, which would later become La7) or newspapers (Il Messaggero). And above all, chemicals, the true bane of Italian capitalism for a combination of reasons, chief among them the delay of large corporations and banks in grasping the changes brought about by the globalization of finance, technology, and production. Segreto is a historian who teaches global economics at the University of Florence and Italian business history at Bocconi. He accessed archives (many documents still need to be unearthed, such as those of Eni and especially Mediobanca), interviewed key figures, and collected a wealth of reconstructions. He recounts the "Berlini system," the Swiss fund that Serafino continued to increase and Gardini continued to drain.

A veritable secret safe that became Raul's ATM, allowing him to finance his adventures, pursue his passions (sailing, throwing money into the America's Cup well; cards, especially poker rummy; luxury with Ca' Dario, the palazzo on the Grand Canal, and so on), and cover his enormous losses, starting with the soybean speculation on the Chicago Stock Exchange that cost him 100 billion lire. And then there were the bribes to fuel politics, right up to the "mother of all the others": 150 billion lire, or perhaps even more, that ended up with politicians, the concrete traces of which have been lost in the mists of rumors and hypothetical reconstructions. But before reaching the tragic end, let's return to the 1980s, the decade of grandiose and unrealistic, courageous and reckless challenges. It was the last period in which Italian capitalism attempted to think big, even if it failed. Leopoldo Pirelli didn't succeed, nor did Gianni Agnelli, who upon his death left Fiat in dire straits; the greats of the past (Pesenti, Falck, Orlando, Lucchini, and all the others, despite Enrico Cuccia's attempts to save those who could be saved) have gradually disappeared; they have deluded and then disappointed the new leaders: Gardini, De Benedetti, Benetton, Berlusconi. Among the many questions to be answered is the legendary ethanol. Even today, it's talked about as a missed opportunity to make fuel greener, but in reality, it could never have become an alternative while oil companies were developing less polluting gasolines, including Eni, which bitterly opposed it.

The most relevant question is whether it was a mistake to take over Montedison, led by a manager, Mario Schimberni, who had the ambition of creating a public company ready to take off on Wall Street. Gardini sold his dream well to the public: a large, modern and profitable chemical company, unlike the past, which had racked up debt, public money, and companies like Nino Rovelli's Sir and Raffaele Ursini's Liquigas, at great cost to taxpayers. Was he playing a trump card or was it another bluff? Did he want to become the largest and most powerful company since Agnelli? Yes, indeed. Did he want to drown the debt in a greater sea? Above all. He understood that a major restructuring was needed, but neither Montedison nor Eni alone were capable of doing it? Perhaps. In reality, he had the ideas and the courage, but not the knowledge, the skills, or the resources for such a vast task. Not even the five-party government, which attempted to engage in gambling without a real strategy, had it. This applies to the PSI, which supported Montedison, led by Schimberni, and to the DC, which supported Eni, even though divided. Ciriaco De Mita favored the tax breaks requested by Gardini to merge and create Enimont, while Giulio Andreotti was the fiercest opponent; and it was against him that "the gambler" who this time had miscalculated his cards ran into trouble.

For thirty years, discussions have been ongoing about liquidating the group, which was dismembered piecemeal. But were there any alternatives? Selling true technological gems like Novamont was a mistake, but what Schumpeterian innovator stepped forward? And wasn't Edison the asset to be extracted and enhanced, as Mediobanca claimed? That it ended up in the hands of the French company EDF is Fiat's fault, not Cuccia, who was already dead, nor Vincenzo Maranghi. Carlo Sama himself had developed a last-minute plan that, by selling everything else, would have kept the agribusiness and, above all, the energy sector, but it required both manpower and money. The banks presented the bill: the Ferruzzis needed to cough up €260 billion for 20 percent of the capital, and they didn't have it. "This was the whole difference with the Fiat case," writes Professor Segreto. "In June 1992, the Turin-based group had financial debt exactly equal to that of the Ferruzzi-Montedison group, 34 trillion lire, and a financial deficit of 10 trillion. The solution was a capital increase of 40 trillion lire. The Agnelli family had no problem finding the resources to subscribe to its 35 percent stake." The lawyer had to accept Cuccia's diktat and, for the first time, share the governance of the company with Mediobanca and Deutsche Bank, further sacrificing Umberto by forcing him to renounce his succession. But he continued for another ten years.

What lesson can we draw? Let's try to establish five points that would be interesting to discuss, potentially extending to the present. 1. Capitalism without capital is a misnomer; the capital existed, but it wasn't in Italy; for the most part, it was located elsewhere, in Switzerland, Luxembourg, or the Caribbean; or it was invested in real estate and financial speculation. This applies to Ferruzzi and many other industrial leaders. Yesterday as today. 2. Keeping one's own resources safe, people have always preferred to borrow from banks, which, at the right time, have called in the loans granted. Everyone has grumbled about bank-centrism, but no one has truly escaped it. And the stock market has also regressed inexorably: in 1999, it equaled a year's GDP; today, it's barely 34 percent. 3. The owner-managed enterprise functioned until the scale of production and the appetite for investment became such that it required different skills, and until foreign markets opened (the last barriers to Japanese cars fell in the early 1990s). Capital that lacked courage could not hold up. You can hand over everything to the managers, as Pirelli did when its cables became Prysmian, a successful multinational. You can bring in a trusted associate, as Del Vecchio did. You can hand over to an heir who can hold together an ever-growing family with coupons, leaving management to professionals (like Fiat to John Elkann). Or you can even identify the right talent among your own offspring, as Berlusconi did. But you have to think ahead and build the succession with strategic vision. If just running around in Ferrari is enough, any dandy will do.

4. Italy, with a few exceptions, has fallen victim to a provincialism steeped in chauvinism (the Made in Italy ideology) and frustration. Over the past twenty years, however, an increasing number of entrepreneurs have internationalized, not only by exporting their products but also by establishing themselves abroad, where customers want the "beautiful things the world likes." This has sparked nationalistic reactions, both left and right, which have weakened the new productive forces and the impetus of what has been called Fifth Capitalism. The return of statism makes matters worse.

5. And here we come to politics. Montedison was steeped in politics. It was born following the nationalization of electricity, acquired by Eugenio Cefis with Eni money and the support of Amintore Fanfani; Mario Schimberni was supported by Bettino Craxi; the Enimont deal divided the parties. Even paying to soften, to silence, to buy silence and assent wasn't enough: no one took responsibility for weakening Eni, not only because it had been a fundamental piece of the Christian Democrat puzzle since the days of Enrico Mattei, but because it was a pillar of the national interest, to the point of becoming a state within a state. Did Gardini understand this? Perhaps, but when he proclaimed "I am chemistry," he committed the worst of all his mistakes.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto