They Took Our Jobs!

The anti-trade protectionists are back in power, and they’re promising once again to “bring back good-paying jobs” that America supposedly had “stolen” from us over the years due to “unfair” foreign competition. Tariffs are of course the preferred tool of protectionists past and present, and President Trump has heralded tariffs as “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” Howard Lutnick, Trump’s Commerce Secretary and influential economic advisor, articulated very clearly in a recent interview that the goal of Trump’s tariffs is to boost manufacturing employment in the US:

Tariffs and rumors of tariffs are sowing doubt, confusion, and fear about current and future US economic performance. This is a shame because Trump’s broader economic policy package, featuring deregulation, lower taxes, cheap and abundant energy, minimizing government waste, etc., would otherwise be strongly pro-growth. Trump’s tariffs are doing to the economy what Plaxico Burress did to the NY Giants, and economists are rightfully speaking out against the counter-productive idiocy of Trump’s shoot-from-the-hip, on-again off-again tariff pronouncements.

Others have spoken well about the economic damage of tariffs. Here I want to take a deeper look into the protectionists’ claims about jobs—losing them and bringing them back. Have we lost manufacturing jobs? Yes. Is this because of trade? Partly. Is it a bad thing? Certainly not. Protectionists commit the classic economic fallacy outlined by Frederic Bastiat:

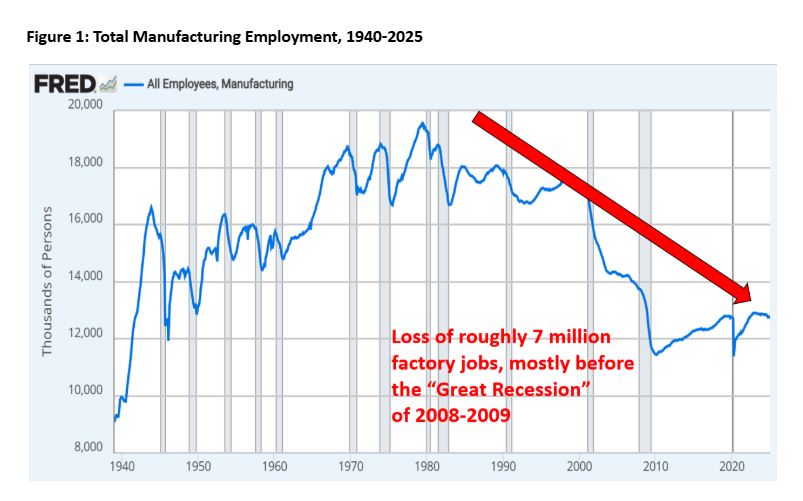

So let’s look at the big picture, beyond the job losses, and assess overall changes in the US economy during this era of alleged manufacturing decline. Fortunately, data makes it fairly easy to see, at least in broad terms, the job-shifting impact of global trade. First, we’ll acknowledge the magnitude of the manufacturing job losses. As shown in Figure 1, manufacturing employment in the US dropped by about 1.5 million from pre-Great Recession levels (2006), and is down by nearly 7 million, or 35%, from the all-time high reached in 1979.

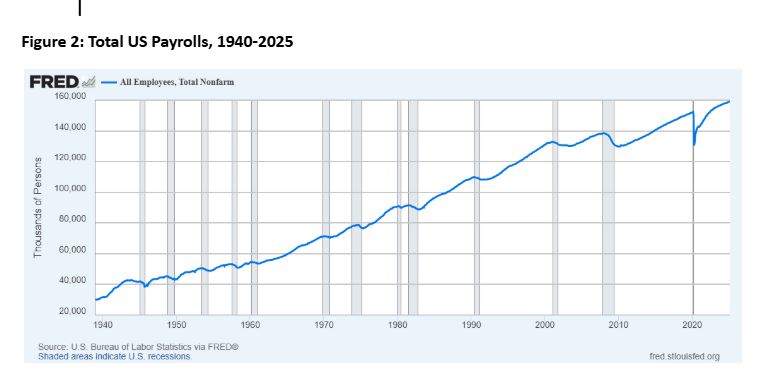

So indeed, the US had been losing manufacturing jobs for decades, despite a small recovery of about 1.5 million from the Great Recession nadir. The overall trend gives prima facie support to the demagogues’ arguments about outsourcing and the so-called “de-industrialization” of America. But manufacturing is just part of an enormous US economy. What do we observe when we look at employment in the entire economy? First, let’s note that total employment numbers wax and wane with the business cycle. For instance, we experienced a shocking and nearly instantaneous payroll drop of 22 million during the Covid shutdowns of early 2020. These losses were fully recovered within two years, though, and since mid-2022 the US economy has been adding jobs on a relatively steady basis. Payroll employment hit a new all-time high of 159 million as of the February 2025 jobs report. The main thing to be observed is the steady and sure long-run uptrend in total jobs, as seen in Figure 2.

Not only are jobs growing, but job growth has outpaced population growth—i.e. the increase in the number of people available to fill those jobs—and this has been the case for most of the last four decades, as seen in Figure 3.

In my next post, I will turn will turn to the question, “Is the fact that more people are working good news for the economy?”

Tyler Watts is a professor of economics and management at Ferris State University.

econlib