Reduce the working day to redistribute growth

The recent decision by the Government to promote a reduction of the working week to 37.5 hours has opened an interesting economic debate in our country. And no wonder, because this measure will affect more than 12 million workers in the private sector (public employees have already enjoyed this workweek for years).

Is it possible to address this reduction in working hours now? Does it make sense to do so? Precisely at this time we can take advantage of the fact that Spain is growing, modernising its productive fabric and gaining weight in strategic sectors to promote this measure. In addition, the reduction in working hours will help to rebalance the distribution of income in our country.

Economists often point out – and rightly so – that countries with the highest cumulative productivity growth are those that can most easily reduce their working hours. Logically, those economies that are more efficient and have high levels of output per hour worked have a greater capacity to generate economic surpluses and use these resources to simultaneously improve corporate profits and wages, while reducing the working day.

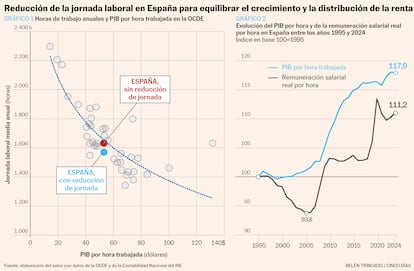

This is precisely what we see in Chart 1 for OECD countries: a clear inverse relationship between both variables. In addition, in this chart we can see the current position of the Spanish economy and an estimate of where it would be in 2025, after the reduction of the working day (assuming that productivity remains constant). It does not seem that, either now or after the approval of the reform, Spain is a rara avis in the context of the OECD.

In recent years, our country has deployed an ambitious reform agenda that is now beginning to bear some fruit. The commitment to maintaining a high level of internal demand – through an expansionary fiscal policy and a continuous improvement in employment – together with the injection of 48.6 billion euros into the productive fabric – thanks to the NextGeneration funds – is driving growth and the modernisation of the economic structure.

Spain is creating one in four new jobs in the European Union. The average size of companies is increasing – firms with more than 250 employees now employ 43% of employees, five points more than a decade ago – and we are witnessing a progressive shift in new jobs towards medium-high and high-skilled occupations. We have closed 2024 with an external trade balance of more than 67 billion (3.4% of GDP), driven by strong growth in exports – tourism, but also advanced services – and by growing energy self-sufficiency – the result of the development of renewable energies. The arrival of foreign investment has experienced annual increases of over 10% since the pandemic and, for the first time in decades, we are seeing how productivity is beginning to grow in a period of economic expansion – in Spain, productivity traditionally remained stagnant in these phases.

In short, the Spanish economy is going through a good period and its productive fabric is showing signs of modernisation – knowing, in any case, that there are still important pending issues. But how are the fruits of this growth being distributed?

We are witnessing an uneven distribution. Corporate profits have been growing by more than 11% annually since the end of the pandemic, and in 2024 listed companies have presented even better results, 20.9% higher than the previous year. However, wages experienced a significant loss of purchasing power as a result of the inflation that took place between 2021 and 2023. This loss has been recovered during 2024, although the recovery is not yet complete.

In fact, this unbalanced distribution of the fruits of growth is nothing new in our economy. We know that in Spain there has been a decoupling in recent decades between the (weak) growth of productivity and the (even weaker) increase in real wages (see the OECD report). Reviving Broadly Shared Productivity Growth in Spain ). This decoupling has led to an increase in capital income significantly higher than that of labour income, thereby polarising the distribution of income at the aggregate level.

Part of this decoupling is explained by the lower intensity of work and the extension of part-time work, as Manuel Hidalgo recently pointed out in these same pages . But, even when we consider these factors and compare productivity and real wages in both cases per hour worked – following the methodology used by the European Commission, the OECD and the IMF to calculate adjusted wage compensation – we see that the productivity-wage gap is indeed significant and persistent (see chart 2).

Reducing the working day is precisely one way to close this gap, modifying the pattern of income distribution to better socialize the fruits of growth. At the same time, it is necessary to continue promoting measures that raise our levels of productivity.

We must do away with the old dogma that wealth must be created first and then redistributed. Reality does not work like that: production and distribution happen at the same time, and the most effective strategies are those that simultaneously boost economic efficiency while rebalancing the distribution of profits in the labour market.

We cannot ignore the fact that the entry into force of the new working day poses significant challenges. We know that large companies have the capacity to cope with this measure without problems, given their current business margins. But the measure may be somewhat more difficult to manage for some SMEs. The parliamentary process is a good time to incorporate those modifications – such as, for example, temporary subsidies in the Social Security contribution – that facilitate its implementation by smaller companies.

Today, the Spanish economy is growing significantly faster than that of our partners. But macroeconomic indicators are not an end in themselves; they must serve to improve the level of well-being of the social majority. It is crucial that the benefits of growth are distributed correctly, creating a kind of shared prosperity. The incipient productive transformation associated with current growth is a good context for undertaking a measure with broad social support, such as the reduction of the working day. Because, let us remember, if public policies do not transmit to citizens the evidence that progress is still possible, they will end up accepting the nihilistic theses that the new reactionary winds bring to the table, with the consequent erosion of democracy.

Nacho Álvarez is a professor of Applied Economics at the UAM.

EL PAÍS